|

Interaction between FAA and Merchant Navy

personnel

|

|

To

comply with the Geneva Convention all the R.N. personnel had to sign on as

deck hands or officers in the Ben Line at one shilling a month (nominal)

and a bottle of beer a day (which we got).Board of Trade specifications

meant that the accommodation was more spacious than on Fleet Carriers,

particularly on the Lower Deck where bunks rather than hammocks were the

order of the night. But though we were all to sail under the Red Duster as

men of the Ben Line, Macalpine was home to two differing seafaring

traditions between which there existed not only rivalries but

recriminations. The differing traditions very obvious if only in the

conditions of work; for while most or the M.N.men worked to Union hours

and rules with overtime for evenings and weekends, our Squadron personnel

were available all hours in all weathers. But on Macalpine, the keynote

was cooperation and both traditions, unified under Ben Line status, joined

together to make Macalpine a happy and efficient ship. Getting on with the

M.N. was not an end in itself but a means to a larger end: the defence of

convoys and those who sailed them against the U-boat menace which had cost

the Allies so much in lives and goods in the early years of the war.

|

|

836 squadron objectives |

|

It

was intended eventually to sail one or two Macships with every convoy.

This would provide close cover from the U-boat threat, it would guarantee

every convoy air cover across the entire Atlantic,and would give freer

rein to shore based aircraft and anti-submarine Escort Groups to seek out and

attack submarines on their way to and from convoys and intensify their

attacks on U-boat and Wolf-packs lying in wait to attack convoys. So 836

became, and was for the rest of the war, committed to the battle of the

Atlantic

and the aircrews who pioneered the first two voyages of Macalpine would

become Flight Leaders of the many sub-flights which made up 836. By the

end of the war 836, with over 90 aircrew, was the largest squadron in the

FAA.

|

|

Early landings on MV Macalpine |

|

The

first the Squadron saw of Macalpine was on 7 May when Ransford made the

first landing with Jim Palmer and P.O. Robertson as crew. By the end of

the day he had completed nine landings. At 1530 he flew the 5th Sea Lord

(Admiral Boyd) to Machrihanish (having disappeared below the flight deck

level on take-off), collected the other pilots who made their first

landings (solo), and did 'circuits and bumps' with varying loads of depth

charge armament before returning to Machrihanish. On the 8th a howling

gale prevented flying, but on the 9th Ransford landed in a 45 knot wind.

On the 14th after Ransford had completed another eight deck landings (one

when with two depth charges on board and his arrester hook torn out by the

edge of the lift - accidentally slightly open - he landed on his brakes)

the Squadron landed on.

|

|

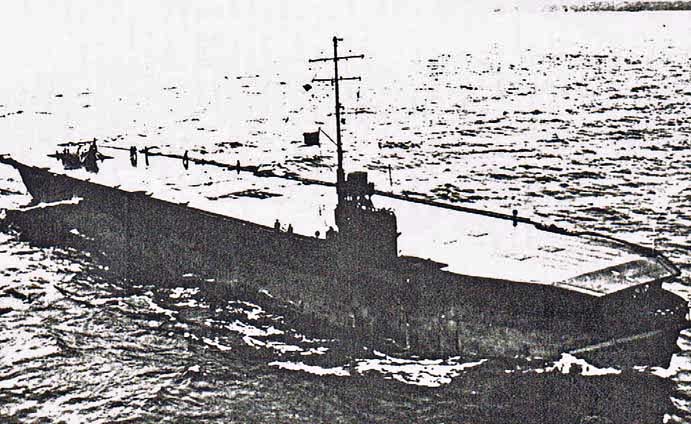

Landing

on M.V.Macalpine- Swordfish going round again-photo from Phil Blakey |

|

|

First deck landings for Observers |

|

For

some Observers Macalpine was the first experience of deck landing. It was

a peculiar sensation to be entirely in the pilot's hands, powerless to

adjust to the heaving fast-approaching deck and knowing that one was about

to go from 40/50 knots to STOP in the space of a second. / recorded at the

time that on our approach, attached to the aircraft by my ‘monkey

strop’ (some called it a G-string) I braced myself for the inevitable, a

marvellous double-entendre line from Sullivan's ‘Crossing the bar’

passed through my mind: ‘I hope to see my Pilot face to face when I have

passed the bar’. But these new experiences merely added to the

confidence between Observer ‘I'll get us back to base’ and Pilot

‘I'll get us down safely’. There followed days in the

Clyde

testing equipment, radio, radar, speeds. Sometimes we moored off Rothesay

or Gourock after a day's trials and there were frequent trips ashore to

Gourock -

Greenock

for stores or spares or dances. These trips in the duty drifter from

Gourock pier sometimes took us no further then the Bay Hotel where beer

was 1/3d a pint! Pilots had reported that as they made their landing runs

over the round down, they felt their aircraft lifted, spoiling their

approaches to the deck. As a result the offending galley chimney which had

exuded the upward draught had to be repositioned A wooden extension was

constructed at the stern end of the flight deck so as to increase the

length available For take-off otherwise the flight deck would effectively

have been reduced by the length of the Swordfish; this was another

modification. Even with fine-pitch propellers for extra lift, every inch

as valuable especially if there was no wind blowing and the ship at

maximum speed was producing a mere 12 knots of wind speed over the deck.

To ensure no unnecessary weight was carried the front and rear runs were

removed, and it was sometimes necessary to leave parachutes and T/air

gunner behind in favour of depth charges

.

|

|

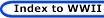

M.V.Macalpine

approaching Halifax, Canada-lift going down. Photo from Phil Blakey |

|

|

Take off & Landing Training |

|

Most

important was the training and practice in flying off and landing on as

quickly as possible so as to minimise the time the ship had to sail into

wind to operate its aircraft. At sea in convoy it was planned to operate

take-off and landing within the perimeter of the convoy and escort, so

time would be of the essence especially if the wind were ahead of the

convoy. So aircraft B had to be in position to land as soon as A's

take-off slip stream had stabilised; deck crew had to look lively to

unhook the aircraft, get it down on the lift and have the lift up in time

for 'C' to land.‘Bats’ Singleton and the Pilots (three of whom had

carrier experience) quickly struck up the necessary rapport and it was

here that Owen Johnstone, the new boy with the natural instincts of a

fighter pilot, produced his special technique, swishing in from port

quarter at sea level and swinging in what some called a 'split arse turn'

in position to receive instructions from 'Bats'.Inspite of inexperience

there were no accidents landing during the whole of our trials.

|

|

Observers Training |

|

The

Observers were far from idle, checking the compasses and keeping an eye on

the ASV serviceability, and practising weather forecasting. They'd been

given a crash coarse in meteorology and weather codes for use at sea and

decisions to fly or not would be based on what they forecast So in the

quiet of the night the 'Duty boy' would go to the Snarks' office and take

down the Morse-coded weather reports, decode the Morse and translate into

met. Code, and plot the fronts, troughs and ridges on the north Atlantic

map. In convoy the forecast was passed to the Commodore and Senior Officer

Escort. There were often red faces for different emotions on the three

ships involved.

|

|

Slater's leadership |

|

In

these compressed weeks of training aboard Macalpine, Ransford Slater was

in his element. Leadership was evident in every aspect. His skill in

unlocking the secrets of how to land on so small a deck and passing them

on to his pilots, the care he took to see that the ‘troops’ morale was

good and to make them feel that their contribution to the success of the

enterprise was vital, and generating a real enthusiasm about the work we

were doing. Not least important was his insistence that RN/MN barriers be

broken down. The 'Royal Navy' logo an the Swordfish was replaced by

'Merchant Navy', the ship’s call sign was 'Dearsden', the home of

Captain Riddle, and the aircraft given call signs Riddle Able, Riddle

Baker, and so on. Later 'B' Flight aircraft were named after the ships of

the Ben Line. The Squadron replaced naval caps with M.N. berets. Phil

Blakey was encouraged to follow his engineering bent with the Chief

Engineer and his Doxfords and listened to Chiefy's laments about the

tension on the arrester wires.

|

|

Doc "Hawkeye" Kearns |

|

Doc

Kearns

made himself master of the anemometer and treated M.N. and R.N.. ‘sick,

lame and lazy’ in a fine sick bay which in retrospect had much of the

air of Hawkeye's tent in M.A.S.H. John Taylor was encouraged (at first) to

learn the ukulele and could soon accompany Ransford in his parody of an

old rugby song:

|

|

|

O we are the fighting Macships

It's at the bar you'll always spot 'em

Our motto is never let up

And to brass hats and bullshit

God rot

'em |

|

|

Personnel on M.V.Macalpine |

|

The

song had all the flavour of Ransford's iconoclasm and irreverence for red

tape and ‘bull’ which we had seen particularly at Machrihanish. As a

Dartmouth

product he never forgot he was R.N., but his approach to achieving the

right tone in cooperation was just right. It was highly successful, with

Capt. Riddle's enthusiasm and good humour, in blending us into one ship's

company. And if we were asked to make cooperation a priority, no-one was

asked to unbend beyond his natural bent, so to speak. Lt.Cdr. 'Tug'

Wilson

as A.S.O. and carrier of the final can while encouraging most if not all

that went on had of necessity to keep the 'reserve' proper to the Senior

Naval Officer aboard. He had already laid the foundations with Capt.

Riddle back in Burntisland one evening, and like the rest of us had signed

on with the Ben Line. He would take part in Bridge and Uckers (Ludo)

contests and be beaten in the final of the latter by the champion - John

Taylor. In truth all contributed to the cooperative enterprise on Empire

Macalpine, and in turn the same spirit was conveyed to the succeeding

grain and oil tankers which went into service later.

|

|

Captain William Riddle |

|

But

over all there presided the commanding figure of CaptainWilliam Riddle. He

was responsible for the safety of the ship and its cargo. He was

responsible for the handling of the ship when operating its aircraft or in

convoy position, and he was responsible for both .R N. and H.N.personnel

aboard and for the harmonious relations between them; a big man in every

way. He set a marvellous example; one can still visualise him leaning over

the bridge, a bulky figure with cloth peaked cap, smiling proudly and

looking as if he'd been operating aircraft carriers all his life. He

had in fact long connections with the R.N.. Born in 1882 the son of a

Provost of Galashields, William Riddle joined the R.N. at the age of 15

and trained under sail, rising to full Lieutenant. He left the Navy in

1911 to be near his wife who died from Bright’s disease in1913.In 1914

he enlisted in the army but in view of his naval career was

transferred to the R.N. in which he served till 1920. Seeing no

immediate hope of promotion, he joined the Merchant Service in the Ben

Line. He was Master of the Bencruachan from 1928 to 1941, when the ship

was mined and sunk off

Alexandria

. Captain Riddle was in hospital with injuries which included a broken

leg, and after a long recuperation was given command of M.V.Macalpine

and

watched her being built at Burntisland.

|

|

So

that with his wide experience of ships and the sea in both services and

his experience of command in war and peace, he was the ideal choice for

this new venture. A brilliant raconteur and bridge player, he was a lively

and entertaining visitor to the Mess when time permitted. Tug

Wilson

recalls the Captain's tale of being accosted on him way back to the ship

in Burntisland by a well-dressed lady offering overnight accommodation -

for a price. Captain Riddle, in civilian clothes and hardly able to

suppress his amusement, boldly offered 2/6d. "Half a crown" the

lady snorted "and me with a hat on". Captain Riddle immediately

had the respect of naval personnel, and he in turn had almost a fatherly

feeling for his young flyers. He richly deserved the O.B.E. which he was

awarded in 1944 for his work in pioneering the Macships.

|

|

Deck Hockey - photo from Phil Blakey

|

|

|

ONS 9 |

|

On 28th May 1943 we left the Clyde and soon the contingents of ONS 9

from Liverpool, Loch Ewe and the Clyde, joined what we believed would be

a perilous and exciting Atlantic crossing. Our role was defensive.

Perhaps it was perceived that Atlantic conditions could restrict the

possibilities of flying from such a small base or lead to unacceptable

levels of accidents which would leave no serviceable aircraft when under

attack: or that too frequent manoeuvring of the Macships within the

perimeter of the convoy might increase the risk of collision. We would

fly dawn and dusk patrols (weather permitting) and fly off in any

weather on receipt of a U-boat contact. But the accent was on defence

against actual attack. Perhaps Macships were seen merely as an advance

on CAM ships in that the aircraft defending the convoy were retrievable

and not, as in the case of the Hurricanes from CAM ships, expendable,

but it was soon discovered that Macships could provide almost continuous

cover when later Owen Johnstone in G Flight, flying from Ancylus did the

night flying trials which instigated night ops from Macships. |

|

To

our great surprise our maiden voyage was a quiet one. In view of the

fierce onslaught by the U-boats in inn winter and spring of 1942/3 we were

expecting the Wolf pack attacks which had been the mainspring of U-boat

successes of those months. Consequently we had our routines with duty

crews at ready in the Ops room and relevant information - weather,

identification - kept up to date. But unbeknown to us, in view of the loss

of 40 U-boats in May 1943 Admiral Doenitz had ordered all U-boats to leave

the

Atlantic

on the 24th - four days before we sailed. Thus, in view of our defensive

role there was much less flying on this trip than in later days but there

was work to be done, locating stragglers and increasingly mounting patrols

to achieve our objective - the safe arrival in

Halifax

of the convoy's forty ships. So the daily routines kept us busy - daily

inspections of the aircraft, plotting the convoy's progress, forecasting

the weather, maintaining equipment, Navexes, and helping the ‘troops’

in preparation for tests for promotion.

|

|

The

first operational sortie from Macalpine was flown by Johnstone-Taylor in H

for Howe (previously Harry). It almost ended in farce. Expecting U-boat

packs to lie in wait, three small vessels were sighted at 0500 hours at

the end of a patrol in cloud and rain, so we dodged into cloud to shadow

and reported what appeared to be three U-boats in company approaching the

convoy. When we came out of the cloud we discovered we were over three

escort vessels looking for ONS 9. They asked us for directions, which we

gave. Fortunately the 1304 R/T set on which we had reported the

‘enemy’ was not working, so our blushes were spared. But we on

Macalpine had had no warning to expect three escort vessels, so

perhaps, in view of the fate of so many convoys our mistake was

understandable. These dawn patrols were preceded by large draughts of

‘Pusser’s sludge’ - a naval concoction made from sugar, cocoa and

condensed milk, stirred into a sludge with hot water. It certainly kept

the cold out in the air on the bridge.

|

|

|

|